From concept to cancellation in 56 hours is a feat, just not one any business wants to talk about, much less have associated with their name. The fallout that comes with proposing an idea that’s met with such a significant backlash that you have to renege on what you planned is the kind of thing that keeps brands awake at night, a horror story repeated to every one who wants to disrupt or invent. Usually, businesses are good with adhering to walking the middle road and avoid drawing ire.

And then there’s the European Super League.

From a brand perspective, the European Super League is the kind of PR nightmare that no amount of spin or publicising can really improve on. Like decorating a sneeze-and-it’ll-fall-off bumper with a sticker, trying to justify the existence of the European Super League in the face of overwhelmingly negative reactions isn’t going to do much except stave off the inevitable downfall.

Which, as of this moment, has happened: the League is cancelled. All the teams have withdrawn.

The European Super League: A brief explainer

On the 19th of April, 2021, the Times published that six English clubs signed up to play in a 20-team-only European Super League. The League, which would have had 15 permanent members as ‘founder clubs’ (12 of which had signed up at the start), would abolish what it viewed as ‘poor quality’ games while also (and this is important) help elite European clubs recover earnings lost during the COVID-19 period. The fifteen founder clubs would govern the competition, and matches would be played both home and away.

The competition would feature uncapped solidarity payments, much higher than those offered by existing European competitors, as well as €3.5 billion to offset the infrastructure costs. Brands such as JPMorgan Chase added extra incentive by backing the competition to the tune of $5billion.

Winnings would be split at: 32.5% to the founding teams, 32.5% to participating and invited teams, 20% on merit, and 15% on broadcast audience size.

On paper, it isn’t a bad idea. On paper, it’s been something in the works since 1998.

What happened?

Pre-COVID, there is every possibility that the European Super League would’ve succeeded.

Post-COVID, the world is trickier.

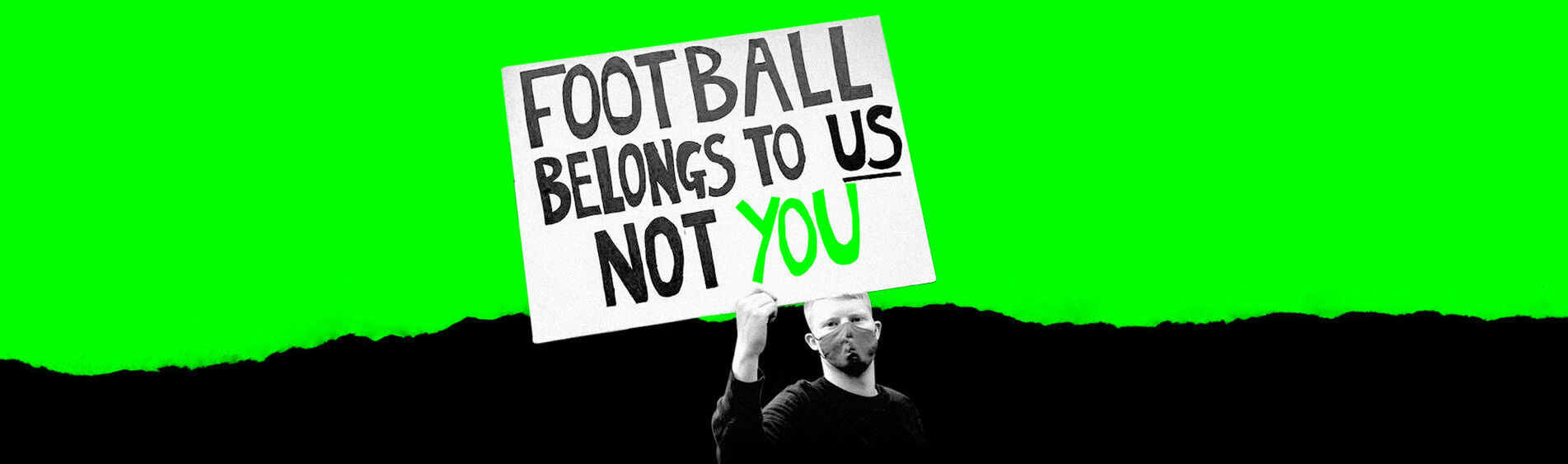

Backlash was near immediate. Everyone from football governing bodies to government entities to avid sports fans spoke out against the creation of the European Super League. Players released written statements. Bans for the competing teams – from domestic, European, and world football competitions – were in the works. Analysts tore apart the European Super League’s plans, pointing out that their proposed hybrid system would lead to a hoarding of the majority of the winnings by the founder clubs, while reflecting back any financial fallout on the rest of the European football teams.

One by one, clubs that had initially been announced as founder members withdrew: first the six English clubs, then Italian Internazionale. With six of their biggest draws down, the Super League released a statement that the project would be ‘reshaped’.

On April 21st, 2021, the project was nearly, if not already, dead.

Two days.

That’s all it took.

But why would it have worked?

Fan support carries a lot of weight.

Think about it in terms of football fanatics. These are people who will travel to see their favourite team in person. Who follow each match religiously. Who spend money on merch. There is nothing as powerful for any brand as a dedicated fan, and football being one of the most popular viewing sports in the world, on paper having a league dedicated and created to showcasing the most ‘valuable’ teams only makes sense.

In theory: football fans would pay for it.

An avid Manchester United fan would visit all the games, both home and away. They’d buy the kit. They’d go to each and every fan event. Because of the play style of the competition, that’s thousands in ticket sales and merch sales, not including hotels and accommodation.

So why didn’t it work?

Fan support carries a lot of weight.

But so does what’s going on.

The European Super League comes on the heels of an entire year and a half’s worth of existing in the same reality as a global pandemic. Not being able to travel, not being able to see and support teams in person, not really having much to look forward to except the idea that, one day, this’ll be behind us and everything will be fine again.

In addition, it comes after a year of the slow realisation of the masses that big businesses and corporations will do whatever it takes to get money – at the cost and the harm of the consumer.

Beyond that, the fundamental tenet of football – that teams qualify to play in important competitions based on merit on the pitch, not based on how much they’re worth or whether they were already purchased a place in the line-up – was forgotten in the bid to create a European Super League and prevent something like COVID-19 from ever cutting back into profits.

Profits earned and kept by teams which already made more money than their lesser-supported European peers.

There’s more.

Most of these teams are ancient, in the sporting world. They have stories and backgrounds and personalities, whether true or ascribed by the fan and later canonised into reality. These stories matter to the fans.

These stories were not taken into account when it came to creating the European Super League. To make an event that capitalised on the bottom line, sacrifices needed to be made – and the sacrifices made was the story behind the brand itself, the story that drew and held fans from the moment they saw their first game to however old they are now.

However, the people who created this League, the owners, don’t see the stories. They see profit. They see a pandemic cutting into their means. They see a crisis to be fixed. The stories are something to be monetised, not protected.

And in ignoring how the teams came to be to create a money machine, they also ignored how important story is to supporting those same teams. When the backlash hit, it wasn’t just for the money; it was for wandering so far from purpose and story that they couldn’t see the point of view of the audience any longer.

In a nutshell

Brands can learn a lot from the European super league fiasco.

Here’s our top five lessons.

- If you have brand values, stick to them. They’re there for a reason. While it might not be evident that fans support you for them, brand values are what distinguishes you from your competitors. Hold onto them.

- Listen to your audience. When it comes to power plays, brands have to bend to the needs of the present and their audiences, or risk fading into obscurity. We all know about KODAK.

- Reach out to your audience. Take their feedback. Listen and do better the next time along. When you listen to your audience, you’re listening to the people who support you the most.

- If you’ve made a mistake, never double-down on it. It’s the worst thing you can do. Apologise with sincerity, move on. The internet won’t forget easily, so give them something better to talk about; redeem yourself with community outreach, with honest change, with visible regret. More than ever, brands are seen as extensions of humanity. So humanise.

- Don’t focus on your bottom line. It needs to be something kept in mind – you need money to run a business, after all – but doing things for your bottom line will ultimately break you if you prioritise your bottom line over your audience.

Most importantly? Don’t drop the very thing that your audience supports you for.

That’s just crazy.