We’re all used to brands behaving badly.

We’re also used to seeing brands do amazing things to create a better world.

Commercial brands of every size and scale exist to turn a profit.

They also exist to fulfil their purpose: the reason that that particular brand, in that particular time, exists. For most, they balance making money with fulfilling their purpose.

But there are brands whose desire for profit supercedes that. Brands who – for one reason or another – operate their business ruthlessly, regardless of whether or not they need to.

Nestle. Shein. Shell.

Apple.

Starbucks.

Brands you might support.

Let’s be clear: this isn’t a singular brand problem. It isn’t tied to a particular industry or subset of brand.

This is a problem that comes up across all industries, and with brands that you have already heard of or might frequent. This is a problem that is borne of a mentality where profit and productivity takes over environmental, societal, or governmental concerns.

In short: this is when brands act like dicks.

Sitting back and letting companies do whatever they want doesn’t help. You might say that neither does writing about it – but calling out the brands that behave badly keeps what they’ve done visible and in public knowledge.

And as we’ve seen over the last few years, the public is powerful. While it might not immediately affect a company’s bottom line, the truth is that bad press sticks around longer than the good, no matter how much good PR pops up on Google – and that it’s in a brand’s best interest to behave better than it did the year before.

Examples of bad brand behaviour

Here are brands who should have behaved better, and didn’t.

1. Pantone

Remember the year when everything was grey? Or lilac? Or blue?

That was because of Pantone.

Pantone is a colour company. It was created to set the standards for how colours should look in print, and, eventually, on digital applications. In time, it started to look at what colours are going to be popular in the coming year and dictate colour trends.Their Pantone matching system helps keep colours looking similar across all spectrums, from print to digital to coated and man-made materials. The Pantone Colour of the Year, a colour chosen to document the feeling of that year in particular, is anticipated by almost every industry looking for guidance in design for future products.

What did it do?

Earlier in the year, Pantone announced that it was leaving Adobe’s suite of products to prioritse the use of its digital platform, Pantone Connect. From October of this year, any designer who wanted to use Pantone’s colours in Adobe products had to pay for Pantone Connect, a subscription service that provides what Pantone calls ‘up-to-date colour information’.

Why does that suck?

Subscription services are nothing new.

However, Pantone’s subscription service doesn’t just affect products going forward. Every PSD file that uses a PANTONE colour – no matter how outdated or obscure – can have its colours stripped and replaced with a black box, to be kept there until the designer subscribes to Pantone Connect. After years of using Pantone without the need to shell out for yet another subscription, Pantone’s turned its back on designers and taken their working files as collateral until payment.

It’s business.

But it’s business done in a way where disagreements between companies impact the users. Subscription services for designers are already a hefty chunk of fees, and to add another one that retroactively removes or changes work based on payment isn’t good business: it’s predatory behaviour that turns a brand into a company ruled by its bottom line.

Source: David Ryder/Bloomberg

2. Starbucks

Starbucks needs no introduction.

Coffeehouse. Favourite of Tiktokers looking to start a new trend. Bane of baristas everywhere.

As an international coffee chain, Starbucks has over 30,000 stores and is one of the biggest coffee companies in the world. Its revenue grows year on year – the current figure for 2022 is 10.98% higher than 2021, and in 2019, it made headlines for the way it helped its baristas through the COVID-19 pandemic. Its coffee is Fairtrade certified and 99% ethically sourced.

What did it do?

Starbucks has been involved in anti-union tactics since the 1980s. There have been unionised workers on and off through the years, starting with the warehouse workers in Seattle in 1985 to the Buffalo workers in 2021 – and Starbucks has consistently and emphatically worked to destroy those unions and to prevent any further unionisation efforts in any of their stores.

This is primarily in the Americas, however, there are unionisation efforts worldwide. In 2021, workers in Buffalo filed a motion to create three further unions, after which Starbucks implemented several union-busting tactics in a bid to get the Buffalo workers to reconsider, including remodeling, shutdowns, closures, and intensive worker surveillance. In 2022, Starbucks continued trying to get ahead of the unionisation efforts by firing upwards of 85 workers involved in the organisation of workplace unions.

Why does that suck?

Whether you fall on the pro or the con side of unions, unions protect worker rights, and companies that combat them also combat those rights: the right to a fair wage, the right to a safe environment to work in, and the right to certain benefits. By creating an environment where the choice is between protecting worker rights and retaining your career, Starbucks has created an internal schism between the brand it puts forward – as a fair, helpful, and supportive brand – and the reality, where its baristas are hounded, surveilled, pushed, and made to state their allegiance to a company that provides less for them than what it promises.

3. Ticketmaster

Founded in 1976, Ticketmaster is a ticket sales and distribution company that fulfills ticket demands for venues, artists, and promoters. Clients can control their events and set ticket prices and Ticketmaster is the platform on which those tickets are sold to consumers. In addition, Ticketmaster also charges several different fees on tickets that are sold on the platform which amount to a significant portion of the overall ticket price, and has been at the centre of several controversies over the years, from partnering with scalpers to inflate ticket prices to enrolling customers into a rewards programme without their say that took them eight months to fully back out of.

But that’s not what’s driven Ticketmaster to the list.

It’s what happened with the 2022 Six Eras Taylor Swift concert that has them here.

What did they do?

On November 18, Ticketmaster put out tickets for sale for the Taylor Swift concert happening in 2023, though within an hour of the sale actually commencing, the website crashed. Consumers online were either logged out or left in a queue that did not move, but several tickets were sold regardless which then wound up on scalper and ticket resale websites.

Fans were infuriated.

Widespread criticism about the platform only increased once Ticketmaster cancelled the ticket sale, citing that it had insufficient tickets to meet the demand, and leaving fans on their own to purchase tickets off of resale websites. However, it’s not the bungled sale especially that drew ire, but Ticketmaster’s increasingly complicated way of buying tickets and the added-on fees that balloon the ticket price by nearly 40%. Additionally, their dynamic pricing model fluctuates based on demand, which means that ticket prices can change rapidly – sometimes within minutes.

Ticketmaster’s previous merger with Live Nation Entertainment has also created a monopoly for ticket sales which exacerbates – not solves – the problem of tickets winding up on resale sites. Currently, Ticketmaster is under investigation for breaching antitrust laws as a result of the Taylor Swift concert bungle.

Why does that suck?

Most brands have a duty to provide a service or a product. The efficacy of that product is up to the brand.

Ticketmaster’s product is a response to a highly lucrative field, one that allows them to make a significant profit over and above the price of a ticket: the added on fees and the exclusivity deals with concert venues has helped them create a monopoly in a market where competition is already rare – and in doing so, have made a situation that is already complicated even more untenable.

And the ones that bear the brunt of it are the consumers.

4. Facebook

Facebook’s been embroiled in controversies and bad behaviours since day one – so this isn’t necessarily new territory for Facebook.

But in 2022, in addition to Facebook’s ongoing problems with its content moderation and the turn towards the metaverse, its war with Apple took on a new facet that is inordinately affecting smaller businesses.

What did it do?

To give you a full idea of what’s going on, it’s important to explain why Facebook and Apple schismed from each other. As leading tech companies, their profits lie in two distinctive categories: for Facebook, it’s advertising.

For Apple, it’s selling their products: the App store, iCloud, Apple Music, Apple TV, the iPhones and iPads and iMacs.

Privacy is important for them both.

It’s also fundamentally important for consumers who are becoming more aware of just how much data about their habits there exists on the internet: data about what they view, what they buy, what companies they favour, what advertisements have the best chance of triggering them to purchase something. Both own a significant amount of that client data – but Facebook uses it to craft ads, whereas Apple retains it for other purposes.

It’s that data usage that has sparked ongoing issues between Facebook and Apple.

What did they do?

Apple has always been big on privacy and on letting users control their own data.

In 2021, Apple released a new privacy feature for iOS 14, App Tracking Transparency, that makes it even easier for users to opt out of app tracking. This comes in addition to the further changes in iOS 15 which allows users to download a report that highlights which apps are accessing permissions and tracking you on iPhone.

For Apple, their privacy slant has only endeared them to users – but for Facebook, it’s the difference between making a significant profit and making far, far less. Apple’s privacy change might not have caused a business slump for Facebook but with only a small percentage of users opting in to allow companies to track you on your device, it’s certainly a prominent reason behind it.

Facebook has lost money over this and is approximately down $600 billion in market value since the changes were made. Additionally, Apple’s new App Store rules also require iOS developers to use inn-app purchases with a 30% commission paid out to Apple – which Facebook and Instagram have never had included in their apps.

As a result, prices have gone up, and Facebook is scrambling to find a way to retain its fine-grained advertising machine without paying out an inexplicable amount of money to Apple. Other companies that rely on user advertising haven’t felt the same pinch as Facebook has, with Pinterest, Google, and Amazon reporting no change to their capacity to reach brands despite Apple’s changes.

Smaller businesses and organisations are the ones who have largely been affected by this. Facebook’s currently trying to find a workaround that will enable them to give some, if not all, detailed information to advertisers looking for the same level of detail as prior to the changes. Additionally, Facebook has also tried to combat Tiktok’s growing popularity by adding in a greater focus on video – which is flooding feeds with content that consumers don’t care about.

Facebook breaking their advertising machine is par for the course at this stage: every adaptation that Facebook has made to its platform usually comes with a few days of businesses trying to figure out how to use it, but compounded with the ongoing algorithm challenges and the stringent rules for Facebook’s business manager, Facebook isn’t really adapting to the changes imposed by Apple well – and providing little to no support on what that means in the long run.

It’s not surprising that Facebook is struggling. Facebook has had difficult years behind them that have made it difficult to continue operating normally – however, it’s never been clearer that the relationship between Facebook and businesses exists solely to provide Facebook with money, and any bumps along the road have to be borne by businesses with no additional help.

5. Twitch

One of the post-pandemic darlings of social media, Twitch is a livestreaming and live video platform that is primarily used for videogame streaming. It gained rapid popularity back in 2019 once Youtube Gaming shut down its standalone games, and a big aspect of Twitch’s specific operations is its partner channels and its support and relationships with specific Twitch creators.

What did it do?

Creators are Twitch’s lifeblood. Without creators, there is no Twitch, and some of the biggest creators on the platform draw in a lot of revenue for the company. Initially, Twitch’s revenue share with its creators was based on a 50/50 split.

By June 2023, Twitch has decided that the first $100,000 that streamers make from subscriptions will be split 70/30, and any amount above that will adhere to the previous 50/50 split.

Naturally, a lot of streamers that use Twitch as a platform have reacted badly or left the platform entirely. Other streaming services such as Facebook and Youtube provide better deals for streamers, which could continue to draw streamers away from the platform and divebomb the community aspect that Twitch has spent the last few years building up.

Community and content creation are two main pillars of the way Twitch operates, so the fact that they’re pushing for greater profits at the expense of the creators who create content for their platform doesn’t just make them greedy; it makes them short-sighted.

Companies behaving better

It’s much easier to find bad news than good.

But it doesn’t mean that there’s only bad companies doing bad things out there. Even the brands we’ve mentioned above have their good moments – just not during this year.

For every company that behaves badly, there’s another that will behave better, set the standards for how corporations should act, and leave the world better than it was.

In 2022, the news about companies behaving badly outweighed the news about companies behaving well – but there are still those that made a difference.

Here are five.

1. Patagonia

A designer and manufacturer of outdoor clothing, Patagonia is one of the original outdoor clothingwear brands, established in 1973 and renowned for its long-lasting products and its environmentally-friendly approach to creating those products.

What did it do?

Patagonia’s founder gave away his company.

We’ve written more about it here, but the gist is this: faced with a growing concern over climate change, Yvon Chouinard decided that the ownvership of Patagonia needed to be transferred out. He established the Patagonia Purpose Trust, overseen by Chouinard’s family and his advisors, and now dedicates every profit that the company makes into combating climate change and protecting undeveloped land all around the world. This is not out of character for Patagonia: since its inception, it has donated money to environmental groups, donated 100% of its Black Friday sales to environmental organisation, and sued the United States government over the suggestion of reducing two protected sites in the United States by 85% and 50% respectively.

But giving away the ownership of Patagonia is more than that. In Chouinard’s own words, the efforts they have made previously have not been enough to fight against climate change on their own, and they need to do more – and what’s more, it starts with Patagonia rather than relying on government and other corporations to start the ball rolling. In a year where many corporations washed their hands of climate concerns by citing it as ‘what can we do’, it makes for a refreshing change of pace – and it makes other organisations, and consumers around the world, see that there is more to be done than just a commemorative Facebook post on Earth Day.

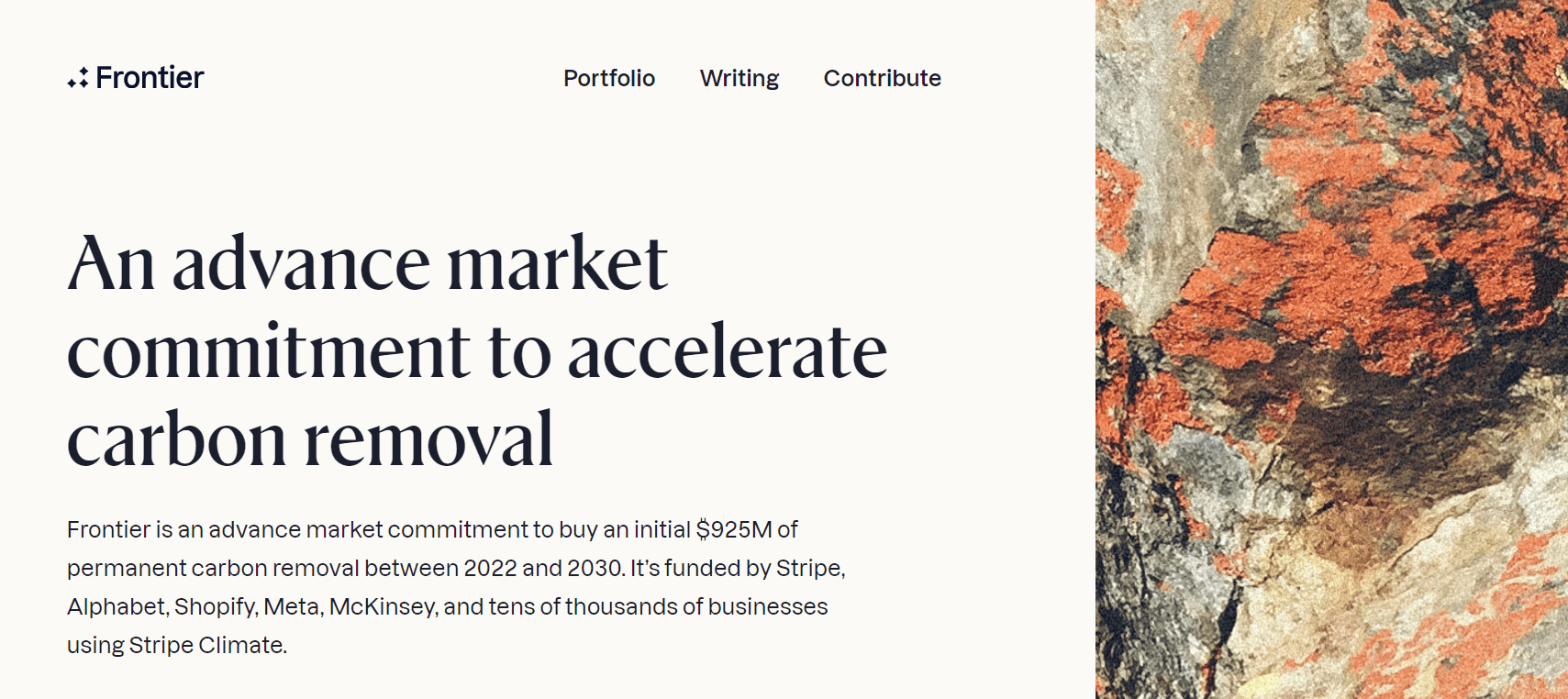

2. Stripe

If you shop online, you might have used Stripe before: it’s an American payments processor and software developer that focuses on e-commerce websites and moblie applications to deliver a safe, secure, and seamless way of shopping online.

What did it do?

Our world is getting warmer. Part of the reason for that is the increase in carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, which traps heat. There are companies that can handle and remove that carbon dioxide, but the process is expensive: far more than the average consumer can afford.

But businesses can afford it. Stripe can afford it.

Stripe announced their subsidiary, Frontier, in 2022. The premise behind Frontier is carbon removal: by purchasing the services of carbon removal companies, they’re hoping to boost and create demand for them, which will inspire other companies to follow suit and also invest in carbon removal. At the time, Frontier has spent about $15 million on realising their vision.

This is only the start. Stripe is one company, and there are gigatons of carbon dioxide that need removal, beyond what any company can afford, and the intent is to patch over the years until governmental policy aligns with environmental needs, and until other corporations start making the same efforts.

Over the next eight years, Frontier will buy over $900 million worth of carbon removal services. It will not be enough – but as a way to signal to other companies that this is technology that exists, technology that is usable, and technology that is needed now, it’s an excellent way to work. And with Frontier set up to put back the money it gains into the products it needs, there’s no obfuscation of what’s possible.

Governments should be handling these matters themselves. Policies and worldwide practices need to catch up to modern day demand.

That they haven’t is through no fault of the consumer. But with businesses, and their billions, behind a renewed push for change, we might yet see a better future.

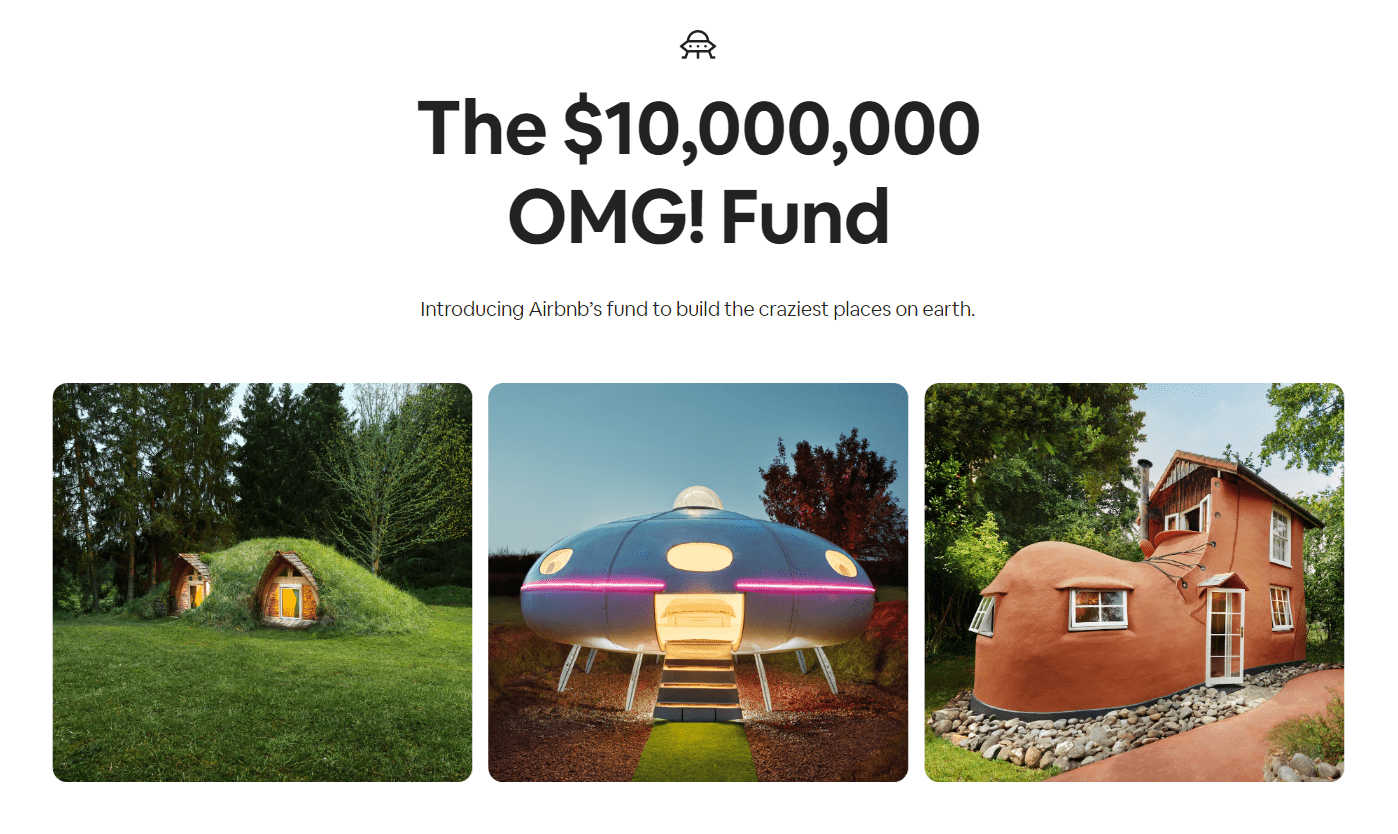

3. Airbnb

Short-term letting and home-letting marketplace Airbnb has had a tough couple of years: the pandemic has slowed down demand, airbnb hosts have been in the news for their overabundant check-out policies, and the lack of regulation over who can be a host has led to a cycle of criticism levelled at the company over the past few months.

Airbnb has still managed to carve out some good in the year.

What did it do?

They’ve set up a cash fund to help build quirky homes.

One of the greatest criticism levied at Airbnb is how the very nature of their operation is reducing home availability and increasing rent prices in desirable areas. As a result, Airbnb has been introducing a slew of new changes to try and gain back some of the goodwill they’ve lost over the past few months. One of those ways is the OMG! fund.

OMG! is a $10 million fund created to support the creation and the building of homes that are a little out of the ordinary. 100 people can win up to $100,000 to design and build their dream location – with the emphasis on the ‘dream’. So far, in the OMG! category, there is a place for Spice Girls fanatic (a Spice Bus renovation from the movie), a place for potato enthusiasts (a hollowed-out six-ton prop spud), and a place for survivalist savants (a giant pod in the middle of Cornwall). Besides providing the funds to build these places, Airbnb also acts as a platform and a middleman the same as it does for other listings, advertising it as part of a specific category for adventurous types. It helps hosts. It helps consumers.

And it helps create the need that Airbnb has crafted a demand for that far supercedes what there is available. While it’s still only a very small start to changing the damage that Airbnb has wrought, it’s stil a start.

And creating a more beautiful world is still something to be celebrated.

4. Ben & Jerry’s

Ice-cream company Ben & Jerry’s has been involved in corporate activism for years. From creating ice-cream flavours to champion different causes, donating their profits to shelters, and founding a grassroots group support foundation, Ben & Jerry’s are the case study for corporate activism that truly tries to make a difference.

What did they do?

In 2022, Ben and Jerry’s started a new podcast: Into the Mix, produced with Voxcreative and dedicated to art, activism, and social change.

Podcasts are an excellent way to get your views out there; they’re accessible to everyone with a device that can support playback, they’re available internationally, and they’re free for the most part. By partnering up with activists who are in the public eye, such as John Legend and Ashley C. Ford, Ben and Jerry’s aren’t just creating another vehicle to advertise how they lean; they’re trying to spark a movement that also looks at the joy of activism, and what benefits it brings you as a person.

And a little good news, especially now, goes a long way. It also adds visibility, especially to kids and disenfranchised youth who are looking for their place in the world.

This comes on the heels of other movements throughout 2022, such as the billboard campaign in coordination with Colin Kaepernick investigating law enforcement budgets and asking state and local governments to reinvest those budgets in programmes for social good.

5. Elevated Access

Formed entirely of volunteers, Elevated Access is a newly-established nonprofit network that has over 1000 volunteer pilots from over 3,000 general aviation airports throughout the United States.

What did they do?

The overturning of Roe v. Wade led to diminishing abortion access throughout the United States: clinics who supply the service have either shut down or have incredibly long wait times, and with fewer available appointments, an already traumatic experience has been made doubly so by the inclusion of travel – sometimes over state lines, and over thousands of miles.

Elevated Access was formed in response. Their organisation, which is entirely staffed by volunteers, has bodily autonomy and freedom to make your own healthcare decisions as the guiding principle of their organisation. Whenever a patient needs to get to a different state, Elevated Access can get them there – for free – to get their gender-affirming and abortion healthcare. Flights are by referral only, but the service is accessible to everyone – and as we’ve stated before, entirely free.

It’s a bold move to set yourself against the government as a matter of personal pride and of doing the right thing, and brands like Elevated Access provide an invaluable example as a brand that was formed just to do the right thing.

Are brands only good or bad?

Absolutely not. It’s a reductive way of looking at it.

Let’s take Netflix.

Arguably, Netflix doesn’t fit into either one of those categories. It has done great things – bringing more content from abroad to Western markets, elevating not just the content itself but the country. Increasing their sustainability measures. Working to create a better product that is available for everyone.

The recent password and ad-supported streaming shenanigans have pissed off a lot of people. It doesn’t make Netflix a bad company: only a company that is really trying hard to survive in a field where it was once at the very height of its game, and is now inundated with competitors with deeper pockets and greater capacity for content. The password and ad-supported streaming tilt is annoying.

But they’re not inherently bad.

For Netflix, it’s just business.

Conclusion

Brands will make the news. It’s whether they make the news for good or bad reasons that sets them apart from each other – and while it has become a lot harder to do the right thing, it’s not impossible, and it’s nothing that brands can’t support.

What separates the brands that make the news for good and that make the news for bad is their intention. Brands aren’t wholesale good or bad (with some exceptions – lasting harm, generational harm, and harm that goes back for years isn’t as easy to wipe out as bad PR). Brands don’t just do bad things or good things and call it a day: it’s the humans behind the brand that make the decisions, and the human being the brands that decide to opt for profit or purpose above other metrics.

It doesn’t mean that brands that value profit over purpose cannot change.

And it doesn’t mean that brands that opt for purpose can’t have a year or so where profit is all they see.

What we can tell you is this: brands need to exist for more than profit. Brands need to do better than the people in charge. Brands have become the shorthand and the primary economic push for policies to go through.

They can make sure that those policies are good ones.

And they can make sure to leave the world better. We have faith in that, if nothing else.