Or a brief look at what AI assistants are doing and will be doing in the very near future.

Artificial Intelligence has the tech world in a twist.

It has those who are not in the tech world but aware of what’s coming in a pickle.

We’ve acknowledged that it is already changing the way we think, the way we work, and the way our jobs are going to be affected within a relatively short time.

Most people you know have at least one browser tab with an AI assistant running – ChatGPT, Notion with its ChatGPT integration, some form of stable diffusion/ midjourney… and we’re not even touching the AI that’s been running our lives as the fundamental underpinnings of Amazon, Facebook, smart banking, and all the other platforms that have deep neural networks integrated.

Just for the sake of clarity, in this article we’re dealing with the AI assistants that we mortals have the ability to speak to. The ones that have what we refer to as possessing a natural language interface.

The AIs that grew to run our world until last year (and continue to do so) needed people with deep knowledge of Machine Learning (ML) to wrangle the neural networks into submission. If you use Facebook, for instance, you may or may not be aware that it depends on ML for news feed personalisation, image and video recognition, translation, spam detection, prediction analysis, and much more.

And as dystopian as it sounds, the idea of an explainable neural network is still being discussed but we’re nowhere near there. This means that while those who build deep neural networks know what they’re asking of the machine and can see what it spits out, they have a very tenuous grasp on what happens inside. But that is another story for another day.

The dawn of the AI assistant

Let’s get back to the AI systems that you and I can easily use.

One way to speak about what’s going on is by drawing parallels with the history of the internet. If you’re old enough to have been there where it started, it will be easy to follow. If you’re not old enough, you’ve got a good handle on the early days of the internet from memes. We’re all good here.

To begin with, everything you’re reading is close to being outdated. By the time the pixels have dried on the last few words of this blog, things have changed. We definitely won’t be making any wild or speculative predictions. We know how that goes.

“I think there is a world market for maybe five computers.”

Thomas Watson, president of IBM, 1943

“I think there will be a cyborg brain in every kitchen.”

Pulling comparisons from the early days of the internet and perhaps even later on in the history of this space is easy because it serves as a historical reference point, a nod to the fact that history tends to echo and reverberate. But history gets more expensive every time it repeats itself. The ones that lose out to this game will do so burning a huge ton of cash the likes of which were not being thrown around in the nineties.

Let’s take a look at the meteoric rise of OpenAI’s ChatGPT. It took days for the news to spread and for a million users to flock to the chatbot, lured by the possibility of a genuinely useful artificial assistant. Within a week we’d found out the staggering depth of possibility it brought with it – it could write code, poems, university assignments, songs, stories and it seemed like we were only scratching the surface. And this is early days. Let’s face it – it is unlikely that even OpenAI had predicted the success. If you’re launching a product, one of the things you do is give your project a friendly name and ChatGPT isn’t exactly that.

We were also very quick to find its flaws. Of course, a large language model has bias inherent to the data set used to train it (and the humans who trained it).

Many of the perceived flaws were user errors. Those who failed to understand that we were dealing with a very specific language assistant and treated it as though an AGI had magically landed were disappointed. Why did ChatGPT suck at maths? Well, it wasn’t trained to do maths so placing an unrealistic expectation on it is the problem of the user not the machine. (Sidenote: WolframAlpha is great at maths but requires plenty of prompt jiggery pokery to be useful so bashing the natural language ability of a GPT-like language model with the mathematical wizardry of WolframAlpha is a matter of time or at least it should be.)

By the time we were happily using the bot for a handful of tasks, a number of things were apparent:

- The training set was staggering in scope but ChatGPT4 was around the corner and will have a model that’s larger by several orders of magnitude.

- The information it had access to seemed to encompass a history of humanity but the information sources ended in 2021 and the model had no access to real-time data.

- The command of the English language was superb, even if the standard tone of voice is rather dull, but the bot started to break as soon as you tried any other language.

- The speed at which the assistant operated was staggering but it quickly buckled under the strain of hordes of users hammering a machine with inherently finite resources.

A tiny technical detour

In the interest of brevity and to stay on topic, we’ll keep the technical aspects of these constraints out this discussion. But it is worth taking a brief detour to see how it takes sustained development and integration of systems to get where we are today and, a little later on this piece, what the immediate future could have in store.

AI got here in leaps. The history of machine learning seems to be characterised by cycles in which one giant leap that is followed by a long ‘winter’. That winter ends when the next leap happens, and so on and so forth.

Sometimes it is a hardware leap – the unexpected use of the GPU as a powerful enough processor to handle the immense needs of ML systems. Other instances are that of an advancement in the algorithm or neural architecture used, and other times we have access to new training sets. Back when ML was in its early days there was no internet so it is easy to see how much easier it is today to gain access to massive data sets we can use to train ML systems.

The transformation that the translator made possible

The most recent leap was the use of a language translator to translate from English to English – from words we speak as part of our day-to-day lives into a code the machine can understand and then back to English that we can read and understand. Hardware has been progressing steadily, leaving the venerable Moore’s law in its wake as it did so and AI models gobble up every ounce of processing power you can throw at them so the story of AI and that of processing power seems to be one that will be inevitably intertwined.

The tussle in the tech world

Back to the dramatis personae, the players on the scene this week and the ones that are shaping up to join the fray over the coming months. We’ve mentioned OpenAI and its wonderful ChatGPT. It has had university professors scrambling to prohibit it, others accepting it with open arms, and put Google into a veritable panic mode. Google actually used the term Code Red and ran back to its founders in an attempt to bring all human brains on deck as the battle with the silicon mind unfolded. And they’ve even rushed an AI event into our calendar during which they’re expected to launch their version of a chatbot. It will be live on YouTube tonight and we’ll update this when we know more.

What Microsoft is up to

Meanwhile, back at the ranch, Microsoft snuck up from behind and integrated ChatGPT into Teams and into Bing. Much is happening in that sentence so let’s break it down.

Microsoft is putting a few billion dollars into OpenAI. Rather than buying OpenAI, MS invested in the company and gained access to a symbiotic relationship with the AI giant. Within weeks, they’d put the gargantuan power of the Large Language Model behind ChatGPT into Microsoft Teams.

This means that after every Teams meeting, participants have meeting notes, action items, and highlights. These are generated automatically – we’re not talking of a simple transcript here – we’re dealing with an assistant that took notes, understood the salient points, and distributed highlights and action items. During the meeting, Teams can show a simultaneous translation of what anyone is saying in almost any language. And while this was a pipedream six months ago, it is already available and included in Teams Premium for $7 a month.

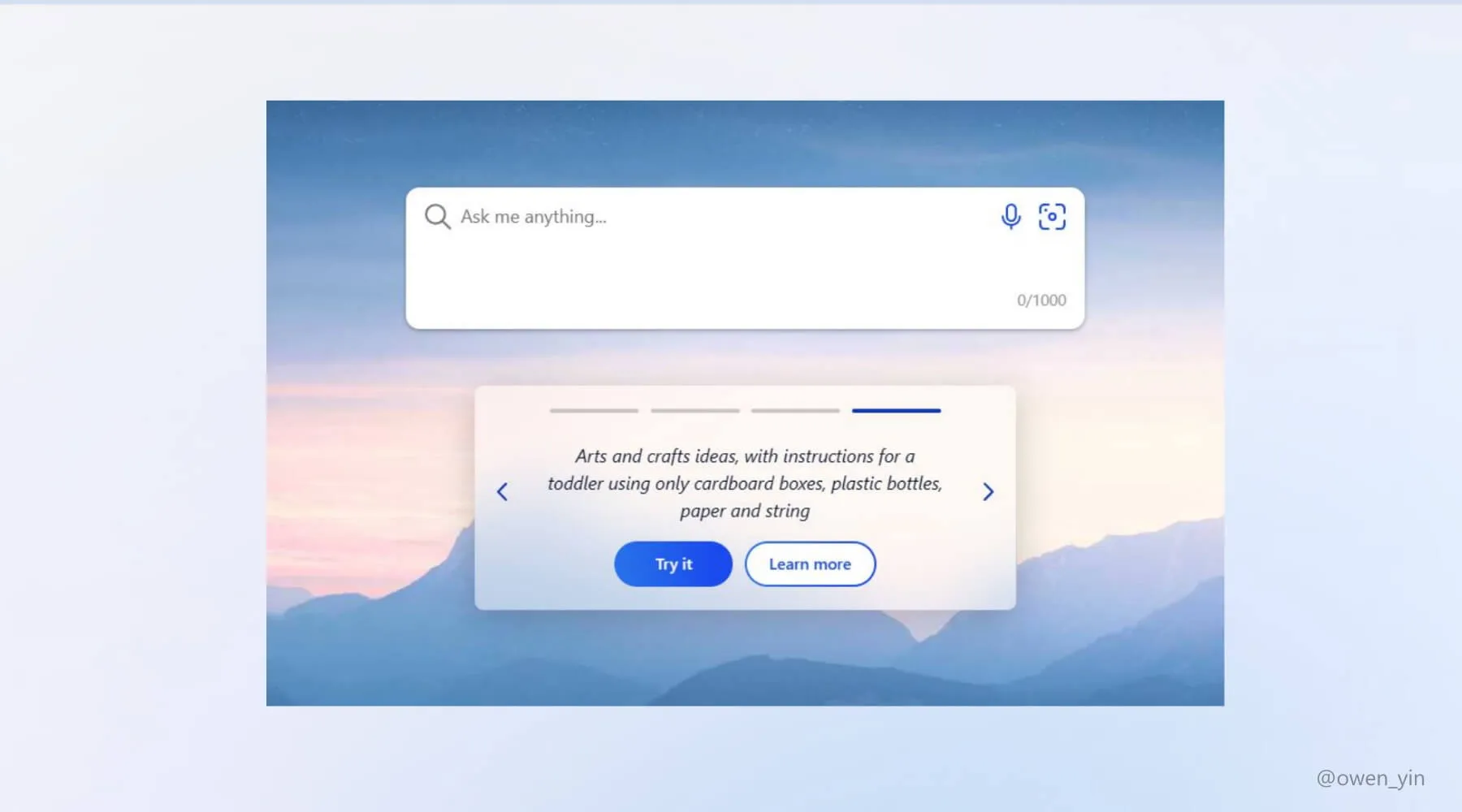

How about Bing? What is Bing, you might ask. It is Microsoft’s search engine, their idea of a rival to Google search that is used by an estimated 4% of the internet. During an event that saw Microsoft and OpenAI CEOs on the same it was confirmed that Bing will be powered by ‘ChatGPT 3.5’ and will initially be available for a few users and on Windows desktop computers only and within Microsoft’s own browser. It stands to reason that one would want a test-bed before unleashing this kind of power to a wider audience. Once this makes it to mobile, there will be no turning back.

Let’s for a moment break down two behaviours. Let’s say you want to buy a car and know nothing about cars. You can run a Google search for cars you should buy, perhaps adding parameters like “small, economical city car”, and then wade through the first ten links on the page of results. Google has, by its magical set of algorithms, presented you with the top ten sites that are most likely to be useful to you and it’s your task to read through pages and pages of articles or watch countless videos hoping to form a useful opinion.

Which, let’s face it, is not a fair representation of our reality.

You have another option. There is someone in your immediate social circles who knows cars, loves cars, and occasionally won’t shut up about cars even after you’ve glazed over. But if you call this person you will save plenty of time reading about a subject you care nothing about in search of a product you happen to need. They’ll know what questions to ask, would have read all there is to know voluntarily, and will zoom in on the best couple of options for you within minutes.

This is what Bing should be like with ChatGPT integrated into the search. A chat-like interface that gives you the power of an advanced AI while being linked to the entirety of the internet for real-time information. Ask a question in natural language and get chatting. Bing should be able to ask you follow-up questions – just like your friend would – to learn more about what you’re after and give you a more useful reply to your question rather than a list of links.

Google has been working on this for a long time but they have been taking their time to make it to the market. They’ve acknowledged that search could be much more useful time and time again, creating BERT, MUM, and other translator-based engines but have been stalling until it’s perfect, ethical, unbiased… and possibly too late.

We’re not predicting the future but it does appear that this could reimagine or supplement the traditional Google-style search sooner rather than later. Those of you old enough to remember the early internet will recall Google turning the tables on those who dominated the search space. We don’t mention Lycos, Altavista, Yahoo, and Excite when speaking about search nowadays but they were the ones who set us up for a searchable internet and they did so by guiding us towards the most appropriate UI and the most useful search results. And Microsoft was clear about their intent:

“It’s a new day in search… The race starts today, and we’re going to move and move fast. Most importantly, we want to have a lot of fun innovating again in search, because it’s high time.”

Satya Nadella, Microsoft CEO, 2023.

Google is determined to stay in the game

Google is making all the right moves as well, with their AI announcement that speaks about them integrating their Language Model for Dialogue Applications (or LaMDA for short) along with a whole lot of other news. That announcement felt so much like Google is really feeling the burn of the openAI launch and media buzz. They’ve been hacking away at AI for more than a decade now, their models made openAI work (remember it was their transformer that unleashed the beast) but they took the cautious route, concerned about a perfect product and an ethical approach. Google has more up its sleeves than anyone, and yet OpenAI simply made the news.

There’s much more to AI than the tech giants though. Anthropic AI is one of the smaller players. Or, to be a little more up-to-the-minute, Anthropic AI was one of the smaller players. It’s claim, one that hasn’t been updated in light of recent events, remains the following:

“Anthropic is an AI safety and research company that’s working to build reliable, interpretable, and steerable AI systems. Large, general systems of today can have significant benefits, but can also be unpredictable, unreliable, and opaque: our goal is to make progress on these issues. For now, we’re primarily focused on research towards these goals; down the road, we foresee many opportunities for our work to create value commercially and for public benefit.”

But Google just dropped $300 million into Anthropic so those down the road opportunities seem to have come to fruition rather rapidly.

But there’s more to tech than the giants

LAION (Large-scale Artificial Intelligence Open Network) is also currently steaming ahead with its open-sourced AI assistant and is actively crowdsourcing training efforts so that anyone on the web can contribute to an always-free model. For those of you old enough to remember MS Encarta, this is like Wikipedia is already in advanced stages of development and population before Encarta had progressed from beta. LAION are working on several models, including image generation models, and they’re all open sourced.

By now you will have noticed that many of the players mentioned were unknown outside tech circles just a few months ago. And the pace at which the new players gain ground is quite staggering.

The image generators

Just look at the image generators. DALL-E, another project by OpenAI, was impressive enough when the beta landed half way through 2022. By the end of 2022, we’d not only seen a flurry of stable diffusion models that put it to shame but also the commercially successful launch of the clearly superior Midjourney. In the space of 6 months we were introduced to generative models and went all to way to an ecosystem that is developing around some pretty impressive technology. There are already some artists selling courses in AI image prompts.

And most of these are still in beta. If you thought there was model bias in language models, you should give image generation AIs a try and prepare for some cringe. So, while we’re on generative models that have been trained on a massive data set, it is early days and we’re all using the same data set.

Hey Midjourney, how about a portrait?

No matter how many times you try, “the most beautiful woman on earth” is always white.

There are already versions of Stable Diffusion that anyone can download and run on their machine – provided they have the hardware to do the heavy lifting. Consider that the latest Mac Mini to hit the shelves of consumer stores has a transistor count that exceeds 40 billion and costs around $1300. That includes a 16-core processor dedicated to machine learning processing. Speaking of Apple and their ML hardware we can’t miss the forest for the trees. So far, their hardware tackles relatively simple stuff like Siri, image signal processing for mobile camera systems, and other relatively low-demand applications for this gargantuan processing power. But Apple is something of a dark horse in this arena. All that power is almost doubtless to be waiting for something significant. Their first all-hands internal in-person announcement since pre-covid happens next week and it’s been dubbed the ‘WWDC for AI’. We’ll update this space once we have more details.

In any case, the massive processing power available to mere mortals means that models, or image sets that can be used to train and generate your own imagery, are about to be a ‘product’ that has unbelievable room for customisation. We haven’t scratched the surface here yet but proprietary models are as inevitable as the stock photo library is. (Or was, depending on when you’re reading this.)

As with all new tech, the early adopters and those willing to put in the hours to learn how to optimise their interface with the tech are those who achieve the best results. But this does not mean that it will be the inevitable trajectory.

Looking back to peek ahead

Once again, we look at the past to hope to understand what’s coming. The early internet was for the tinkerers. It was for those who knew how to make the damn thing work and what port the internet box thing plugged into. That didn’t last long. Great technology is initially indistinguishable from magic. Then it becomes even better when we stop regarding it as technology because it becomes easy and pervasive.

This step has already happened. Writing this into Notion means we can hit /Help me write and ask for help with practically anything. MS Teams, whatever Google is coming up with next, and the tech that the rest of 2023 will bring will be instantly usable to everyone because it took all of six months for a natural language interface with AI to go from tinkerer-only to general public.

AI has the tech world in a twist but the tech world has always been in some twist or another. There have always been Kodaks and Nokias and Myspaces and Palms. What we can’t say is if there will always be Apple and Google and Microsoft and Meta.

That is up to us. We, the users of tech, get to pick what we want and it isn’t always what’s the best from a technical perspective (BluRay has much better picture quality than Netflix) because we adopt what’s convenient, is in the right place (usually our phone), does the job, is priced well, and doesn’t need much technical knowledge to use it.

We can’t possibly predict what’s next but we’re watching the space attentively. And we’re doing so from a number of angles. From the lazy/optimist perspective, we’re glad to have machines that will help us do the work we do, that can act as technological prostheses that carry on from the limit of our mental capacity and extend it beyond where we thought possible.

From an ethical standpoint, we do hope that the tools that are headed our way will be equitable in that they will be available to all. We mentioned Wikipedia as a great example of this, a sign of the internet times that is a shining beacon of crowdsourced and publicly available knowledge. We look forward to seeing the next evolution of AI inhabiting a similar space.

There will be winners and there will be losers.

We the users will be winners as AI becomes more ubiquitous, more useful, and dare we say, more open. The losers will be the tech giants that don’t play their cards right. Unfortunately for them, this game is one where the rules are still being written, where the dice have a constantly changing number of sides, and to which players can simply join unannounced and mid-game.

We just can’t wait to see how it all unfolds.