Or how we can work with machines or get out of their way

AI is going to take our jobs. AI is a bubble. Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) is just around the corner. AGI will never happen.

In reality, there is a little truth in all of the statements being made about AI but neither can be completely accurate because, like every industry caught in a frantic rush of development, it is impossible to see where all the pieces will land.

The AI space is vastly unpredictable

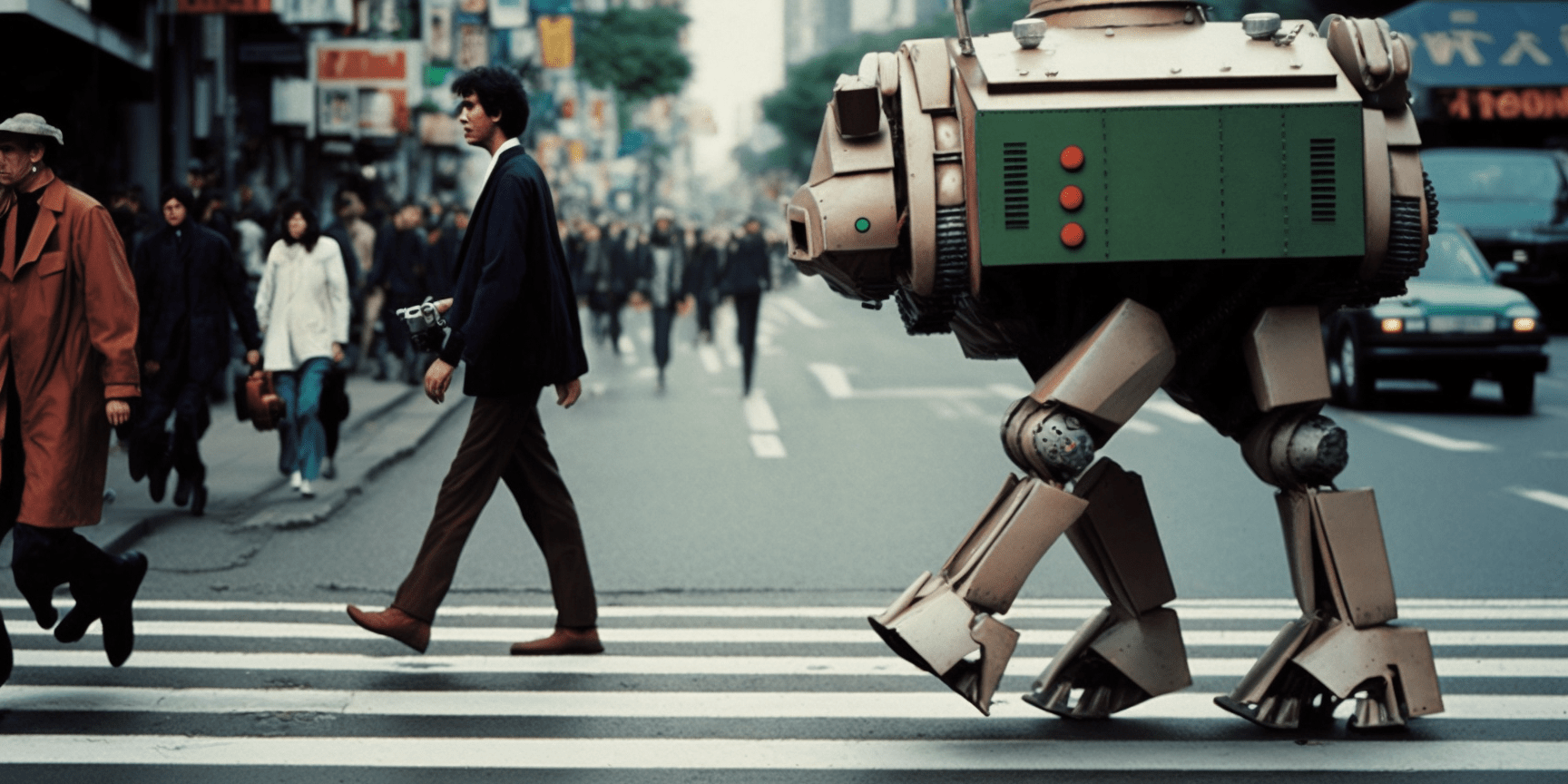

Even when the pieces land, the landscape will shift. AI isn’t a destination. It is a journey that our species will forever be intertwined with. We didn’t stop inventing machines when the Industrial Revolution had blown its last puff of steam. We kept inventing and aggregating. It’s unlikely that the inventors of the steam engine would have predicted Boston Dynamics and their robotic dogs but we can trace the lineage from one to the other.

Perhaps even more pertinent is the nature of the industry and the complex web of moving parts that it encompasses. Medicine, finance, search, advertising, aviation, energy, blockchain, imaging… the list of activities impacted is multiplied by the number of technologies being developed by all the established tech companies, universities, startups, and even individuals to leave us with so many moving parts that we can’t really nail anything down.

To add another layer of unpredictability, we must not forget that we are dealing with an intelligence. It keeps surprising us and bewildering is as we develop it. The idea of a predictable or explainable AI continues to largely elude us. While we know what we ask of an AI and can see what results it gives us, the inner machinations of deep neural networks that we have developed is too complex for us to understand. Add to this the “oh shit!” notion that we are using AI to develop better AI and it should cause us to pause for a moment before deciding that we know what’s next.

If there is one certainty, it is that this industry will keep surprising us.

Let’s look at jobs. As horrible as it sounds, some jobs are almost immediately at risk. And these are the ones, quite predictably, that most commonly resemble the tasks that the newly emerging AI models perform so well. But first, we need to have a shared understanding of what AI we’re referring to.

So what’s an AI in this context?

Let’s for a moment qualify what we mean by an AI.

An intelligence can be described as any entity that has the ability to choose a better outcome from a possible list of outcomes. The more intelligent this entity is, the more outcomes it can choose from and the better equipped it is to pick the best possible one. Using this model, an ant is not as intelligent as a mouse, and a mouse is not as intelligent as a human.

Humans have a broad spectrum of intelligence types – the same person can ride a bicycle in a city, write a novel, peel an orange, and flirt with another human using subtle, non-verbal cues. And the same human can generalise intelligence very quickly. We only need to burn our fingers once to know to avoid all flames, no matter what the source of the fire is.

Artificial Intelligence and the neural networks they run on, at least the ones we have access to today, work differently. They take a huge amount of training to generalise knowledge. Tesla have billions of miles of training on their self-driving car models to approach a reasonably good driving AI while it takes a human a few hours of lessons to achieve the same ability.

And they have a narrow spectrum of intelligence. The AIs at our disposal are really, really good at one thing. They are far superior to any human at that task but that’s all they know.

Armed with this knowledge, we can make a few assumptions about what tasks we will be passing on to AI or at least working with AI to help us do our job much better.

AI will help us do our jobs (and relieve us of annoying ones)

Let’s take a day in the life of a content writer or a designer. The day is usually split into many different ‘jobs’ or tasks. There’s some time dedicated to research, some time dedicated to thinking and putting ideas together, and some time devoted to actually creating something new. But there are also parts of the day that are relatively repetitive – the kind of tasks that we do without really needing to think too hard.

Let’s say a beautiful piece of artwork has been created. Now it is time to resize it to fit a pretty standard set of assets.

Or a wonderfully crafted blog post has been written and now it’s time to summarise it into brief captions for a handful of different social media platforms.

Both of these can be offloaded from our mind and given to a machine that has learned how do one of these tasks and to do it quite well. It’s been trained, by assigning weights to successful outcomes, to perform in a way that we like best. It is equipped to learn our preferences and to keep working that way. So, both of these creatives can work side-by-side with an AI and spend the time they’ve saved just enjoying their lives.

Now if there is a person whose job it is to do just the task that’s repetitive and that we would rather give to a machine to do, then that person’s job can be replaced by an AI. This is not to say it will, but it is possible.

But let’s take a plumber. They come home and troubleshoot the most bizarre of faults that we, messy humans, create in our own homes. They use their experience, their tools, their hands, and their ability to take instant decisions on the most practical outcome to get the job done and restore order and harmony in our homes.

Carry this over across all jobs that require skill and we can see that these jobs are safe for now. It will take us a while to implement the broader kind of intelligence needed to do these jobs and to build the robots it takes to give this general intelligence a useful corporeal form. To be more precise, the tech we need to build this robot probably exists, scattered around industries and intellectual property licenses, but it would cost as much as the GDP of a small nation to put one unit together and that’s not good business. For now.

It’s the mid-level white-collar jobs that are at stake.

Wherever there are groups of people in a bullpen doing what is mostly repetitive work that can be passed onto an automated system with a narrow but deep intelligence, the likelihood is that the populations of these bullpens will be the first to start thinning. Whether this is a good thing or not is up to your personal ethical standpoint and the subject of a significantly deeper discussion than this brief blog can go into.

A good point of departure is to think of the fate of the ecosystem around horse-drawn cabs at the dawn of the popularity of the motor car and work your way up from there.

We’re all coders

For a long time – meaning for all the time that computer code existed and all the way until a few months ago – programming a computer to do your bidding was the reserve of the coder, the software engineer, the guys and girls who knew languages that were esoteric to the rest of us. Now, we can address some of the most powerful computers out there by just typing a sentence into a chat box. In essence, every time we ask a chat-enabled AI for something, we are writing a little single-serve app and asking it to do our bidding. The more creative we are, and the more complex the task, the more useful and productive is the result of our interaction.

This means that natural language is already the de facto programming language. And as the AIs available to us get even more powerful, the need to use the programming languages of old (they’re so last week) will dwindle into obscurity. If you’re a sub-par coder, you’d better watch out because there’s a grandma out there doing a better job than you are and all she had to learn was how to write in English.

Symbiotic relationships are desirable

When we think of symbiotic relationships we usually go to that bird that eats the insects on a crocodile’s back as an example. The bird is fed and the crocodile isn’t itchy so both live quite happily. It’s an old definition of symbiosis but for the sake of this article we can put up with eye-rolling of biologists.

The happy relationship we’re referring to is the one between carbon-based lifeforms (us) and silicon-based brains (Artificial Intelligence).

The abilities of the systems that are available to us are quite staggering. They far outstrip the ability of any one person because they have been trained on gigantic models, huge data sets that represent the collective effort of hundreds of thousands of humans. They run on GPUs (the computers that power AI) that just love parallel processing and do so at outrageous speed. This means that, unlike us, they think of multiple things at the same time and do so thousands of times every second.

The highest ideal is, therefore, a human-machine tandem. A carbon-silicon creature that thinks with the value system and ambitions of a human and does so at the speed of a machine, drawing on a data set that is much broader than any amount of swotting for exams can achieve.

Think back to the industrial revolution. A lot of back-breaking work done by humans was replaced by machines that didn’t suffer and that could be significantly stronger than any one human. One man can carry one brick for so many metres but a steam engine can carry many, many bricks for as long as you can feed it coal.

What you want to be in that situation is able to drive the train or perhaps to repair it.

It takes skill to get the most out of any device, and AI assistants are a perfect embodiment of this maxim. Consider a camera. The same camera in the hands of an experienced photographer and in the hands of a complete novice will not produce the same photos. Give me the full set of paintbrushes that Michelangelo painted the Sistine Chapel ceiling with and I will produce an unholy mess that no pope would bless.

Embrace the race

Leaps in technology follow a pattern that echoes the one that came before. We’ve seen figures that show how long it took for radio to reach 80% of households and how that time was much shorter for TV, and even shorter for mobile internet.

And there is a pattern in the narrative, too. Early adopters tout a new tech as a panacea, gilding the advance with an unrealistic set of expectations of what it will do. Laggards and those afraid of change are vocal in their objections, with a handful of versions of ‘this tech will never catch on’ or ‘this tech is evil and should not be allowed’. While both positions are heartfelt, neither is entirely true of almost any innovation.

Photography purists are bemoaning the fact that some artists won photography competitions and immediately after they did, they admitted they’d created the images using Midjourney. What they’re angry about is that they didn’t have the ability to discern the difference themselves. ‘AI art isn’t art’ is an echo of the reaction that artists who had honed their skill at oils on canvas had when photography was invented. They argued that ‘photography isn’t art’ because photographers hadn’t bothered learning how to use a paintbrush. If an inkjet print of a photo fetches a couple of millions at the better galleries, why would an NFT of AI-generated art not do the same?

Midjourney won’t be replacing Saul Leiter’s colour work but it can already create passable street work that, at a glance, is coherent and convincing.

It is up to every one of us to land on the side of this story that is committed to history. A sensible place is to embrace the race, to get acquainted with the immense potential that these emerging technologies have to offer while being acutely aware of their limitations. This allows us to stretch the tech to its maximum, harnessing its power to make our lives easier and the output of our work even better. It also keeps us from falling into the trap of unrealistic reliance on a tool that has its inherent limitations.

Once again, this is an echo of past wins and losses with new tech. The ones who said new tech will never catch on died like Kodak did. The ones that put far too much faith in new tech died like so many of the tech startups at the dawn of the internet. The ones that embraced change and pivoted are still doing what they set out to do. We don’t think of IBM as International Business Machines any more but that’s what they are and they remained true to purpose. From cash registers when those were relevant to desktop PCs and laptops and all the way to Watson, they weren’t married to a specific technology but considered their purpose as delivering the machines that ran the business of the day.

We speak about being true to purpose at every opportunity. We also speak about business agility until someone tapes our mouths shut. But they are two maxims that have historically led to robust, sustainable business models.

Opportunity and agility

Opportunity lies in what you are already doing for your customers. Agility means you can remain valid to them, no matter what changes happen around you. Having your purpose clearly in mind means that you can be valid for as long as it takes us humans to evolve into a different species and that will take a while.

This means that to stave off redundancy, we need to be absolutely sure of what we are giving our customers. Let’s take Amazon as an example. They offer low prices, a wide variety of goods, and rapid delivery. Three fundamental pillars that humans will always want. In the words of Jeff Bezos:

“I very frequently get the question: ‘What’s going to change in the next 10 years?’ And that is a very interesting question; it’s a very common one. I almost never get the question: ‘What’s not going to change in the next 10 years?’

And I submit to you that that second question is actually the more important of the two – because you can build a business strategy around the things that are stable in time. … [I]n our retail business, we know that customers want low prices, and I know that’s going to be true 10 years from now. They want fast delivery; they want vast selection.

It’s impossible to imagine a future 10 years from now where a customer comes up and says, ‘Jeff I love Amazon; I just wish the prices were a little higher,’ [or] ‘I love Amazon; I just wish you’d deliver a little more slowly.’ Impossible.

And so the effort we put into those things, spinning those things up, we know the energy we put into it today will still be paying off dividends for our customers 10 years from now.

When you have something that you know is true, even over the long term, you can afford to put a lot of energy into it.”

This could be one interesting approach about your business to keep in mind in the face of a sea of uncertainty: What’s going to be constant in your space over the next ten years? What fundamental human need do you serve? Therein lies your opportunity and it takes all the agility you can muster to dance to the changing landscape and keep your operation relevant.

What should we be doing about AI?

If there is something we’ve learned about tech it is to never say never. ‘Never’ stems from fear of change. It is a wholly unrealistic standpoint and this is more true today than ever. The money pouring into silicon that can think is staggering. The parties at play mean business – quite literally. The quicker we accept and move ahead at the right pace the better. You don’t want to be the company that said “We don’t need to be on Facebook because it will never catch on.” Neither do you want to be the investor who put all their eggs into MySpace. But you do want to watch this space with a healthy balance of caution and optimism. Caution about the unrealistic claims and optimism about what machine learning systems can bring to your business.

If you’re recruiting in areas that are repetitive, consider investing in tech instead because automation of anything we humans do more than once will come sooner than we think. This isn’t new – automation has been around for almost two centuries now – but now it takes a deeper meaning. It goes beyond a simple ‘if this then that’ and delves into repetitive decision-making within narrow or specialised fields, especially when this thinking involves drawing on an overwhelming dataset.

Whatever your area of practice, there are Machine Learning systems being developed or already deployed, albeit at varying stages of maturity. Seek them out. If they appear underdeveloped or the results are as yet sub-par don’t dismiss them. Use them for inspiration. Riff on them. Perhaps more importantly, learn about them while they’re still embryonic and allow your learning curve to naturally grow with the tech.

When those who have taken the option to wait for some unspecified time in the future to figure out where the dust will settle, you want to be miles ahead. You want to have found the best way for silicon brains to do your bidding. The prosthetic superpowers we were promised in sci-fi narratives since Jules Verne put pen to paper are finally within reach. We’d be fools to leave them to others.

All images were created using Midjourney.

Here’s a little exercise. If you’ve gone through the cycle of being amazed at what ChatGPT 3 (and now 4) can do and then realised that it’s writing is completely devoid of humanity, read a paragraph of this blog at random and try and spot what it is that makes you think it was written by a human and not by ChatGPT. Put a reminder in your calendar for one year from the day you read this. On that day next year, look up a handful of blogs and do the same. Odds are you won’t be able to make this distinction any more.